|

In 1934, when she was 18, my mother was thrown out of the house by her father because she

was pregnant. He didn't want the shame and instructed every member of the family never to

speak to her again. She moved around looking for work, cleaning and scrubbing floors, with

her baby Margaret. I was born in 1940, when she was living with a man who beat her. Mother

left that man and we moved around again until she died of TB in 1948.1 was found in the room

with her dead body. Goodness how long I'd been there or what state I was in.

I have all my papers and I know then that Margaret and I went to stay in a small village north

west of Newcastle called Ponteland where there was a workhouse and asylum. It was a terrible

place. Around this time my sister Margaret went to live with a vicar and his family and

was later adopted. Eight years ago I went back to Ponteland with my grandson. It is now

offices for the Northumbria Police and one of the officers there showed us around. When I

saw the back of the building I felt dizzy and couldn't breathe. I nearly collapsed - though I

didn't know why it had evoked such a strong response in me. We went to get a cup of tea so

I could regain my composure and then I apologised and said I didn't know what had happened.

The policeman told me I had nothing to apologise for. He said that other people who had

come back to visit had had a similar reaction. It was obviously a place of terrible memories.

We had no papers so nobody knew who we were, but somehow my grandfather was traced.

He said he had no daughter and no grandson. He never visited or saw me, and signed me over to Barnardo's.

In 1948, soon after my new life began at Barnardo's. I was sent to Stepney with a chaperone, who hardly spoke to me. I had to wait

in a large room full of other children and their chaperones. I was then examined from head to foot and sent to the store to get some

clothing. I remember it so clearly as though it was yesterday. I was literally terrified. The building was huge and dark and no one

explained why I was there or what was going on. I remember the first night as my most frightening ever, being left alone in a room

high up in the attic. I cried myself to sleep.

The next day I was taken by my chaperone to Boys' Garden City at Woodford Bridge, with its lovely wee cottages. It was possibly

one of the best days of my life. We had food - my first taste of mince and potatoes -and had a glass of milk before sleeping in our

own beds, four to a room. It felt as if the sun had come out. We were treated like children and to me at the time, it was the best place

on earth.

For someone who had virtually lived on the streets, I can remember the details so clearly. I remember the line of poplar trees, the l

ittle fences, the grass, the trees and the flowers.

Later I was sent to Abingdon, where I deteriorated psychologically. The couple who ran the home, Mr and Mrs Gibbon, had a

Victorian approach. He even wore wing collar shirts. It was like a military establishment. We were known by numbers, not our

names, and we were put to work constantly, cleaning the house and clearing the grounds. We were marched in military style to school

and back each day.

In 1951, the superintendent and his wife just disappeared and were replaced by Walter and Edith Brampton. They were the complete

opposite and ushered in a new era. They had a son and a daughter of their own and they knocked down a wall so we could all sit at

one dining table together. Mr and Mrs Brampton sat half way down the table with us boys and their children

around us. It was awfully strange for us and, at first, we had a lot of suspicions, but they were absolutely marvellous. The house had

a family atmosphere. It must have been very difficult for them, as we must have been some of the most aggressive boys around.

We were not used to anyone.

They even raised money through another charity to take us away on holiday. I remember sleeping on the floor of a village hall for a

few nights and going- to the seaside. They gave us pocket money and allowed us to walk into town. The three years at Abingdon with

them were absolutely marvellous.

Finally I went to Goldings, where I learnt the printing trade and took to it like a duck to water. Then at 15, Barnardo's moved me on

into lodgings and an apprenticeship. I felt incredibly lonely. I actually had nobody. At the end of the working day everyone went

home to their families, but I could either walk the streets or go back to my room. I became depressed and felt suicidal at times.

In Barnardo's, you are a member of a group and as a child you cling to the feeling of being secure within that group. I decided to join

the navy and that felt the same. I felt fine for a long time, but the feelings of loneliness and depression crept in. For two weeks, when

we had annual leave, I had nowhere to go.

It was at a dance hall in Plymouth where I met the girl Mary who became my wife. We married in December 1963, in snow and

blizzard conditions. Moving to Scotland, where she was from, I worked driving a "shunting" lorry and bulldozer. Then I saw an advert

for a hospital, looking for ex-servicemen with knowledge of security. I applied and started working as a nursing assistant. It was a

psychiatric hospital, in those days more like an asylum run by prison staff. I learnt so much there though and was seconded to another

hospital to become an Enrolled Nurse, going on to train as a Registered General Nurse in my 30s. I became a Charge Nurse, finally

working as the Senior Clinical Nurse for Forensic Psychiatry for the Secretary of State for Scotland.

Mary and I had two daughters and worked hard to improve our way of life. In 1976, my wife

became sick with kidney failure. She became ill again in 1998 with breast cancer, so I stopped

work to look after her. By 1999 she'd had a mastectomy and was much better so I started

working again, this time as a builder with my daughter's partner. We built extensions, everything.

When people ask me about Barnardo's, to put it bluntly, I say 'they put a stick up my backbone

and made me stand up straight'. Without these homes, children like me would have been lost.

The older I get the more I appreciate what they did for me.

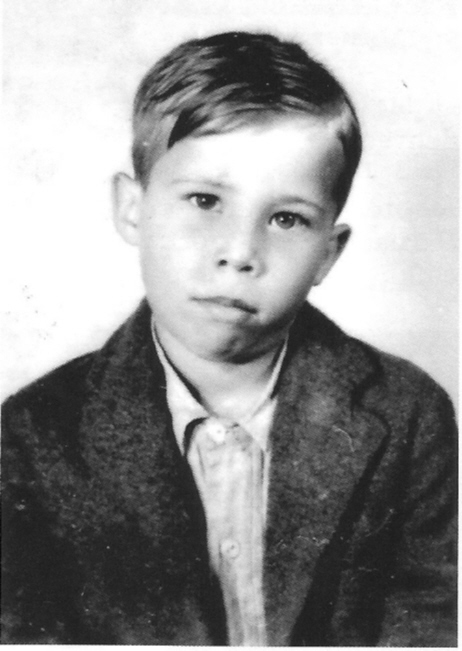

David Swinger Boys' Garden City 1948 Abingdon 1949-53 Goldings 1953-55

|

of d swinger 2016a.jpg)